This month I was all over the place: starting shows and then getting distracted, making leeway on my TBR pile and then bringing more stuff home from the library, and generally just working very haphazardly through everything. But there was some good stuff here this month, especially the long-awaited release of Carnival Row and The Dark Crystal prequel, both of which were on my radar, and neither of which disappointed.

I also rediscovered a pulp fiction trilogy from Caroline B. Cooney that I hadn't read since adolescence and held up surprisingly well, a new trilogy from How To Train Your Dragon author Cressida Cowell, and the latest (at least until this month) from Philip Pullman, which I've been looking forward to for SO long.

It was also the month of Aladdin, in what was already the year of Aladdin.

A pretty good month of material all things considered!

Losing Christina Trilogy: The Fog, The Snow, The Fire by Caroline B. Cooney

I must have been twelve or thirteen when I read this trilogy for the first time, and it was in a rather jumbled way: The Fog and The Fire were available at the library, but it was a while before my sister discovered The Snow at a secondhand book shop. So coming back to it all these years later, it was a relief to experience it in the correct order, and in one consecutive go.

I must have been twelve or thirteen when I read this trilogy for the first time, and it was in a rather jumbled way: The Fog and The Fire were available at the library, but it was a while before my sister discovered The Snow at a secondhand book shop. So coming back to it all these years later, it was a relief to experience it in the correct order, and in one consecutive go.

Christina Romney is a thirteen year old girl who lives on Burning Fog Island (named for a trick of the light that makes it appear the island is on fire) off the coast of Maine. She's about to attend school on the mainland for the first time with several other island teenagers, and they're all going to board with the principal of the high school and his wife: the Shevvingtons.

As much as Christina is looking forward to it, equating high school with maturity, the Shevvingtons are a nightmare to live with: outwardly reasonable and polite, but psychologically manipulative in private. Christina's friend and fellow islander Anya is soon under their thrall, gradually losing her sense of identity in the wake of their relentless gas-lighting, and naturally nobody believes Christina's claims of what they're up to.

It's a harrowing story, and I remember it well all these years later: Cooney holds nothing back when it comes to the horror of the Shevvingtons, the way they can manipulate public perception, psychologically torture their charges, and paint Christina as unhinged and paranoid in a way that has everyone believing them.

It wasn't until this reread that I realized what an incredible character Christina is: wild and stubborn, two qualities which make her just about the only person who can withstand the Shevvingtons' torture, even as Cooney explores her excruciating vulnerability. Watching her give up things she desperately wants, whether it's a skiing outfit or her chance at being popular, in order to stand up to the Shevvingtons and protect their more vulnerable victims, is heartrending.

Cooney is also good at capturing the eerie atmosphere of the seaside town, and the elements that provide the trilogy's titles are vividly invoked.

Each story can get a little repetitive (all of them end with Christina and another of the Shevvingtons' victims trying to escape imminent danger) and the conclusion a little anti-climactic, but I loved revisiting this. It's pure pulp fiction, and yet there's an edge to it that clearly resonated with me as a young reader, considering how many details I managed to retain.

The Tunnels of Targoola and Crooked Leg Road by Jennifer Walsh

I grabbed these two books off the library shelf thanks to their tantalizing titles. I mean… the Tunnels of Targoola? Crooked Leg Road? Those are the things unsupervised pre-adolescent adventure dreams are made of.

They turned out to be fairly average stories, though not bad by any means. You know those books which are so pleasantly bland and blandly pleasant you can’t really think of anything to laud or criticize to any great extent? That’s what you’ll find here.

The first deals with a quartet of young teens finding a network of tunnels under a derelict mansion that’s scheduled for demolition and redevelopment, though their exploration gains the unwelcome attention of land investors who seems to have a vested interest in the property (that is, even more than you’d expect). Drawing on clues from a slightly doddery woman in the local rest home, the kids begin to wonder if there’s a treasure down in the tunnels somewhere.

The first deals with a quartet of young teens finding a network of tunnels under a derelict mansion that’s scheduled for demolition and redevelopment, though their exploration gains the unwelcome attention of land investors who seems to have a vested interest in the property (that is, even more than you’d expect). Drawing on clues from a slightly doddery woman in the local rest home, the kids begin to wonder if there’s a treasure down in the tunnels somewhere.

The second involves the same teens growing increasingly aware of a menacing group of men in the neighbourhood, who again seem to have an unhealthy interest in their movements and whereabouts. When one of their number suddenly disappears, the others grow convinced that he’s been kidnapped, and start putting together clues to deduce his location.

Only one of the four protagonists really pops as a character (honestly, I couldn’t tell the boys apart) though the Australian setting makes for an interesting change of pace – even if the author can’t resist a few digs at the kiwi accent. They’re light and diverting reads, but don’t go out of your way to find them.

The Book of Dust Volume 1: La Belle Savauge by Phillip Pullman

Reading this was like settling back down with an old, beloved friend. I first read Northern Lights when I was thirteen years old, and it was one of the most formative reading experiences of my life, not only shifting my perception of what fantasy could be, but leading me to greater, more complex questions about theology and faith.

Reading this was like settling back down with an old, beloved friend. I first read Northern Lights when I was thirteen years old, and it was one of the most formative reading experiences of my life, not only shifting my perception of what fantasy could be, but leading me to greater, more complex questions about theology and faith.

Its most distinctive feature is that it's set in an alternative world where people's souls exist externally from their bodies, in the form of animals. There are all sorts of rules governing this concept, such as daemons "settling" into a single animal once their human reaches maturity, or the touching of another person's daemon being a terrible taboo, but the interesting thing here is that it's no longer a crucial part of the story.

In the original trilogy the existence of daemons were central to the plot, being tied in closely to the overarching theme of growing up and gaining full consciousness. Here, they're mostly just a component of world-building, albeit a fascinating one, and if anyone were to start the series from this book, they might be confused as to their point.

In any case, La Belle Savauge takes place when Lyra (the original trilogy's protagonist) was just a baby, and being cared for by the nuns of St Rosamund priory. Living just across the bridge is Malcolm Polstead, a young tavern boy, who becomes devoted to Lyra after meeting her while doing odd jobs for the sisters.

Divided into two parts, the first deals with Malcolm gradually awakening to the political upheaval going on around him, with Lyra seemingly at its centre, and the second with Malcolm using his boat La Belle Savauge to survive a terrible flood and transport Lyra to safety. A fairly straightforward story all things considered, but told with Pullman's careful prose, insightful commentary, and amazing world-building (though it does delve into some surprisingly traditional fairy tale tropes towards the end).

Readers of the original trilogy will recognize familiar characters and the network of agendas they're pursuing, though Pullman seems to have mellowed a bit when it comes to his depiction of organized religion. Although the Magisterium and its agents are still the main antagonists, the nuns of St Rosamund are benevolent - even heroic - and their faith seen as a positive component of their lives.

It's fun to see the drama that surrounded Lyra long before she was able to realize it, and just how many people were embroiled in her fate right from the word go. Pullman deepens ideas that were only briefly touched on in Northern Lights (for example, the witch prophecy, the locations of all the alethiometers, the interest the church took in Lyra's whereabouts) and gives us glimpses into the activities of the gyptians, Mrs Coulter, and Lord Asriel - though in that last case, he's rather more heroically characterized here. Did Pullman forget he ends up murdering a child?

Still, it was great to return to this world - and there's another book to look forward to!

The Wizards of Once, Twice Magic and Knock Three Times by Cressida Cowell

I'll admit it was the amazingly beautiful cover design of these books that caught my attention, moreso than knowing they were from the author of the How To Train Your Dragon series. To be honest, I'm not a big fan of "comedic fantasy" (such as Terry Pratchett, don't kill me) but the first page of this book was tantalizing in its description of the medieval forests of Britain: "as twisted and tangled as a Witch's heart."

It also has a pretty good hook: the Wizards (basically, the Druids) and the Warriors (that is, the Romans) have been fighting for generations, with the former trying to defend their lands and the latter encroaching further and further with the help of their iron weapons - the only thing that magic has no effect on.

In the midst of this conflict is Xar, the youngest son of the Head Wizard, a boy who has no magical abilities at all, and Wish, the daughter of the Queen of the Warriors, who is in possession of a magical object she wants to protect at all costs.

Naturally the two of them cross paths, and of course they realize the solutions to their problems may be solved if they work together. Each one comes with an entourage of friends (sprites, snowcats, squires, at least one giant) and the culture clash begins as soon as Xar and Wish decide to join forces.

There aren't a lot of surprises here, for as soon as Cowell introduces the threat of Witches you know that the story is leading towards an alliance between the Wizards and Warriors in order to defeat them, and our gang of intrepid heroes is currently tracking down the ingredients of a spell that might defeat their common foe in what is a fairly straightforward quest narrative.

Yet there's also some poignancy as well, as when the children realize there's a history between Xar's father and Wish's mother, or when their assorted companions work together out of love for their friends/leaders. Despite the presence of the type of humour designed to make children laugh (body odour, pratfalls, people turning into weird creatures) I have to admit I want to see how it all ends - which won't be for a while yet, as despite my assumption it was a trilogy, there's going to be at least one more instalment.

Rear Window (1954)

Let's deal with the elephant in the room: Alfred Hitchcock was a ghastly man who terrorized his actresses, and I fully believe Tippi Hedren's account that he sexually assaulted her on set of The Birds and Marnie.

Let's deal with the elephant in the room: Alfred Hitchcock was a ghastly man who terrorized his actresses, and I fully believe Tippi Hedren's account that he sexually assaulted her on set of The Birds and Marnie.

He's also been dead for nearly thirty years, so it's not like he's going be benefit from me watching and enjoying his work. Everyone has a different threshold when it comes to the relationship between bad people and the art they create; I'm okay with watching Hitchcock, whereas Woody Allen and Roman Polanski, I avoid like the plague.

My knowledge of Rear Window extended to a) the general premise: a man recuperating from a leg injury sees what he thinks is a murder through the apartment window opposite his, and b) the fact The Simpsons did a riff on it in the episode where Bart believes Flanders has murdered his wife.

Given my understanding that Hitchcock was a misogynistic wretch, I was actually pretty surprised by the treatment of women throughout the story. Granted, he takes a dim view of matrimony (the murder victim is a nagging wife, the newlyweds next door eventually start bickering, and it's pretty obvious that James Stewart and Grace Kelly's relationship is doomed to fail).

And yet with Stewart confined to a wheelchair with a broken leg (complete with emasculating imagery such as a smashed camera on a nearby table), it's up to Grace Kelly and the insurance nurse (played by Thelma Ritter) to perform the more hands-on investigative work. At the film's climax, when Grace Kelly is put in mortal danger, all Stewart can do is impotently writhe in horror.

The camera never leaves Stewart's apartment, making it an incredibly controlled and limited setting, which is nevertheless bursting with colour and life. You get a real sense of the apartment buildings and their inhabitants, and the camera angles from Stewart's POV are inspired. When looking out the window, we can only ever see what he does.

Great movie; I can see why it's such a classic.

Aladdin (1992)

My rewatch of the Disney Princess films continues, though this one is interesting considering it features the only princess in the line-up who actually isn't the lead (or at least the co-lead) of the film. Yet for all of that, Jasmine is still an engaging and vivacious heroine, who - look, I've already made her Woman of the Month back in March.

My rewatch of the Disney Princess films continues, though this one is interesting considering it features the only princess in the line-up who actually isn't the lead (or at least the co-lead) of the film. Yet for all of that, Jasmine is still an engaging and vivacious heroine, who - look, I've already made her Woman of the Month back in March.

I've also already written a pretty long post on how much I love Aladdin and Jasmine's love story, so I'll try and keep this brief.

For all of the well-deserved acclaim that Robin Williams and the Genie's animators got, he's not the only thing that makes Aladdin a great movie. In fact, it's worth pointing out that his character doesn't even turn up until about the forty-five minute mark.

It's the genuine likability of the lead character combined with a fatal flaw (characterization that possibly wasn't seen again until Woody and his jealousy in Toy Story) that makes Aladdin so good. In Aladdin's case, it's his lack of self-esteem and subsequent selfishness that drives an important plot-point - namely, that he fails to keep his promise and free the Genie when given the opportunity, giving Jafar the chance to steal the lamp, and leaving Aladdin to deal with the consequences.

There are a few hiccups in the narrative though. The lamp-seller at the beginning was originally meant to be revealed as the Genie in disguise (he's also voiced by Robin Williams) but since this was axed, the character disappears completely after the intro (unless you count his eventual return in the straight-to-video Prince of Thieves, which admittedly, is a pretty impressive book-end).

There's also the weirdness of the whole Chosen One narrative, which is actually completely unnecessary. Apparently Aladdin is "the diamond in the rough" which makes him the only one worthy of entering the Cave of Wonders, though the rules surrounding his entry and that of the thief at the beginning of the film are inconsistent (Gazeem gets chomped immediately; Aladdin has to traverse the interior without touching anything. It seems a little unfair that the test of character is so different).

His Chosen One status is meant to justify Jafar's meddling in his life, but it would have worked just as well if the reason Jafar approaches him in the prison cell is the exact reason he gives: "I need a young pair of legs and a strong back to get it for me." I mean – what’s the point of the Cave of Wonders only letting Aladdin in, if the lamp can just be taken off him the second he emerges?

And does this mean that the Genie's last master was also "a diamond in the rough"? That seems unlikely considering the Genie is still a slave to the lamp when Aladdin meets him.

Setting aside all this nitpicking, Aladdin IS a diamond in the rough, as demonstrated by his willingness to give away bread he spent the entire opening number trying to steal to some hungry children. He's the best Disney prince, no contest: a bad boy who is a good man.

And of course, he wins the day by using his street smarts – not only in tricking Jafar into becoming a Genie, but surviving a rolling turret by positioning himself in the window, and being agile enough to avoid Jafar when he shapeshifts into a giant snake. I remember being so impressed with all this when I was a kid, and it's one of the few movies that wants you to believe the hero is a good, smart, worthy guy, and so actually puts the work in to SHOW us this.

Beauty and the Beast may objectively be the best of Disney's animated canon, but I think Aladdin is probably my favourite, and the one I come back to when I'm in need of cheering up.

Corpse Bride (2005)

This movie, along with The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline, make a fairly natural spiritual trilogy: all have links to Laika Studios, Tim Burton and Henry Selick, and each one builds a dark, Gothic ambiance with a few genuinely scary moments along the way.

This movie, along with The Nightmare Before Christmas and Coraline, make a fairly natural spiritual trilogy: all have links to Laika Studios, Tim Burton and Henry Selick, and each one builds a dark, Gothic ambiance with a few genuinely scary moments along the way.

And yet of the three, Corpse Bride is the least renowned – not surprising considering its truly macabre story, which I’m certain would have never been greenlit were it not for the fact it’s based on Jewish folklore (perhaps Tim Burton pitched this by insisting that it would have educational value?)

Victor van Dort is engaged to Victoria Everglot, a betrothal arranged entirely by their parents: one wanting access to high society, and the other desperate to refill their coffers through an alliance with the nouveau riche. Against all expectations, the young couple take a shine to one another, but Victor runs away in humiliation after he forgets his wedding vows during the rehearsal.

Away from such a judgmental audience, he’s more confident practicing in the forest, where he places the ring on an unturned tree root (this is the detail that comes directly from Jewish folklore) that is actually the protruding finger of a dead maiden, who rises from the earth with the belief that Victor has just married her.

Now Victor has to find his way out of this morbid love triangle, which is complicated by the arrival of another suitor for Victoria’s hand.

Corpse Bride is an odd duck. I mean…a children’s movie about an undead bride, the responsibilities of matrimony, and the relentless gloominess of day-to-day life? That’s quite a sell, and like I said – if it wasn’t based on a pre-existing folktale, I doubt it would have ever been made.

But made it was, and perhaps its best detail is that the world of living is gloomy and bleak, while the land of the dead is colourful, cheerful and filled with music. Yet some of the world-building is a little slipshod, especially regarding movement between “upstairs” and “downstairs.” Passage from one to the other is talked about in hushed tones, as though it’s a huge deal – and yet Victor, Emily, and eventually everyone are constantly doing it over the course of the film.

And given that the realm of the dead is such a warm, pleasant place, where everyone seems to know Emily by name, you have to wonder what exactly she was doing lying in the woods with her arm outstretched. I mean, she was obviously there for a while. So how is she on familiar terms with everyone down below? And then at the film’s conclusion she dissolves into butterflies, which is quite another representation of death altogether.

There are a few too many supporting characters, whose antics seem designed to stretch out the run-time of a very slim plot, and a couple of the songs (though catchy) could also be cut (though only the incomparable Danny Elfman could have: “that's why everything, every last little thing, every single tiny microscopic little thing must go according to plan” as lyrics.

These are largely nitpicks, but I wonder if they’re the reason Corpse Bride didn’t quite have the cultural impact of The Night Before Christmas and Coraline. If nothing else, it’s worth it for the stop-motion animation, the eventual solidarity between Victor’s romantic rivals, and the eerie beauty of the Victorian village and snowy forest.

Aladdin (2019)

I had a vague idea that once Disney had exhausted its supply of animated films that could be adapted into live-action cash-grabs, I could binge-watch all of them and then do a master post of how much they all sucked in comparison to the originals - but having travelled to Auckland for my birthday to see Aladdin on stage, it felt like this should be the year to watch the latest big-screen version of his story.

I had a vague idea that once Disney had exhausted its supply of animated films that could be adapted into live-action cash-grabs, I could binge-watch all of them and then do a master post of how much they all sucked in comparison to the originals - but having travelled to Auckland for my birthday to see Aladdin on stage, it felt like this should be the year to watch the latest big-screen version of his story.

So... live-action Aladdin. Honestly? This movie has no reason to exist. It's pointless and uninspired in every respect. The actors are leaden, the costumes and set-designs garish, and there's nothing - NOTHING - here that wasn't done first and a million times better in the 1992 film. It's almost amazing how inferior it is.

Okay, there was one tiny improvement: when Aladdin first comes across the carpet, it's trapped under a rock in the Cave of Wonders. He frees it, demonstrating his kindness and giving the carpet a reason to help him out. But that's it!

The structuring in particular is awful, with Jafar and the Cave of Wonders introduced during the last bars of Arabian Nights, Aladdin and Jasmine crossing paths almost immediately (without the story bothering to build them up as distinctive characters) and no escalating stakes in the grand finale during which all of Aladdin's allies are incapacitated with Jafar's magic. There's no giant snake, no hourglass trap, instead everyone just stands around awkwardly in a courtyard while Jafar monologues.

Jasmine rendering Aladdin speechless by pole-vaulting over the roofs is replaced with her hesitating and panicking, the apple trick that gives Aladdin away is replaced with him just brushing Jasmine's hair away from her face, and the all-important "do you trust me?" question is a throwaway line.

In just a few potent scenes in the cartoon I was sold on the idea that Aladdin was in love with Jasmine and best friends with the Genie. Here there's no chemistry between the former and just a bunch of bad jokes between the latter. How do you drain the charisma from Will Smith for heaven's sake?

Also, they give Jasmine a girl-power subplot about how she wants to become Sultan for the sake of the people (though we never see her interact with them in any significant way), sings a power-ballad about how she's forced to remain speechless (even though original flavour Jasmine never had a problem with speaking her mind) and passionately beseeches the palace guards not to betray her father (which is immediately undermined when Jafar just wishes to become a sorcerer instead).

They also give her a handmaiden in what I can only suppose is a failed attempt to pass the Bechdel Test (they only ever talk about men) and whose presence completely undercuts Jasmine's isolation and loneliness.

It's just utterly uninspired on every level, but as long as people keep paying money to see 'em, Disney is gonna keep churning them out.

Batman: Hush (2019)

I enjoy these one-shot Batman films: they’re standalone, they’re well animated, and they usually have a pretty compelling story to tell – even if they require foreknowledge of who all these characters and their relationships are. (Damien throws me a little every time I see him).

I enjoy these one-shot Batman films: they’re standalone, they’re well animated, and they usually have a pretty compelling story to tell – even if they require foreknowledge of who all these characters and their relationships are. (Damien throws me a little every time I see him).

Despite the presence of a masked criminal with innate knowledge of Batman, who forces the Rogues’ Gallery of Gotham into doing his bidding, this is really a movie about Bruce Wayne, Selina Kyle, their alter-egos and why they can’t be together. The answer is that… Bruce is a dumbass.

Okay, so that’s not really the answer they were going for, but – honestly. At the climax of the film, Bruce has the Riddler suspended over a walkway, and refuses to let go of the cable that’s keeping him from falling to his death. Realizing the building they’re in is about to explode, Selina cuts the cable herself, and the two run to safety. So it’s a nice twist that instead of the inevitable breakup being because Selina falls back into bad habits, it’s because Bruce is so committed to his “no kill” policy that Selina genuinely considers him certifiably nuts.

What Catwoman (and therefore the writers) fail to mention in the moment, is that if she hadn’t sent the Riddler to his death, if Bruce had stayed in the building, then he would have absolutely, 100% been killed. The entire place explodes mere milliseconds after they escape. She incontrovertibly saved his life.

And of course it’s good that Batman has a no-kill policy – but in proving his commitment to it, the film just makes him out to be suicidal. I mean, along with the fact of the Riddler murdering Bruce’s friend, digging up his corpse, and rigging a trap so that when Batman arrives at his lair he’ll trigger a mechanism that will swing his friend’s dead body down from the ceiling and into his face, there is a limit to how much you owe a dangerous criminal before it’s considered totally acceptable to step back and save your own life.

So… I’m with Selina on this one. As she points out at the end: she was willing to change and become a better person for his sake, whereas Bruce wasn’t able to become a more sensible one for hers. Not yet, anyway.

Foyle's War: Seasons 4 - 7 (2006 - 2013)

Watching four seasons of something in one month may seem impressive, but this is British television, and so the whole thing in total was comprised of only ten episodes (some of these seasons were only two episodes long).

Watching four seasons of something in one month may seem impressive, but this is British television, and so the whole thing in total was comprised of only ten episodes (some of these seasons were only two episodes long).

I picked this up from the library as part of my continuing "finish what you started project", and again enjoyed the very slow-paced and stately police investigations that take place during and just after WWII, in which all manner of men and women take advantage of the upheaval and confusion of wartime in order to profit.

I found myself appreciating Foyle a bit more this time around: his moral compass is absolute, and in a world when I'm growing increasingly tired of the excuses and justifications made for all manner of vile characters, watching a man who deeply cares about justice for the victims of crime is a true breath of fresh air.

That said, one and a half hours for each episode is way too long, and the writing struggles a little for Sam and Milner after the war ends (they're mostly relegated to semi-relevant subplots once parting ways with Foyle). But it's always fun to see familiar faces amongst the guest stars, usually before they go on to bigger projects: Andrew Scott, Fiona Glascott, Sean Harris, Tim Pigott-Smith, Charlotte Riley, Zoe Tapper, Joseph Mawle, Phyllida Law, Eleanor Bron - it's always fun seeing familiar faces about ten years before bigger roles came along.

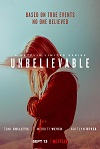

Unbelievable (2019)

This is a tough watch considering its subject matter, but a rewarding one. My hot take is that rape has no pressing need to be in any work of fiction that isn't a) specifically about rape and b) prepared to tackle the subject with sensitivity and seriousness. If not, it's something that can easily enough be implied without any on-screen depiction, or avoided entirely.

This is a case of the former, which involves two investigators looking into cases of rape occurring across state lines, which they realize early on have very similar MOs. Along with their investigation, we follow the fallout of one of the rapist's many victims, a vulnerable young woman who is failed utterly by the police force when her claims of being attacked are deemed false.

The key feature in the telling of the story is that the investigators (played by always-brilliant Toni Collette and lesser-known Merritt Wever, who I've never seen before but who is similarly excellent) and the youngest victim (Kaitlyn Dever) never cross paths, only communicating via telephone call at the end of the final episode.

As you might expect, there is a huge emphasis on the way the female investigators handle the case compared to their male colleges, from the greater compassion and sensitivity they demonstrate, to their unquestioning assumption that victims are telling the truth.

That said, it's not a simplistic case of "man bad, woman good" either - for instance, it's Marie's foster mothers who first cast the seeds of doubts surrounding her rape claim, and an inexperienced male intern who figures out a crucial puzzle piece. It strikes a good balance in the gender roles, even as it creates an underlying sense of exasperation when depicting the flaws in how so many male cops handle the situation.

There's a bit of a red herring introduced early on that had the potential to be very interesting: the women float the idea that their culprit might be a cop given that the attacker is so adept at leaving no trace behind him, an idea that seems to be backed up when Marie is prosecuted for filing a false report (which her lawyer tells her doesn't often happen, suggesting someone trying to scare her into further silence), but they back away from this fairly quickly, perhaps opting to avoid a more convoluted narrative about police corruption.

It has a relatively upbeat ending, though I could have handled a bit more bittersweetness. Obviously it's a good thing that the women get justice, but it's also feels a little too neat, even taking into account that the culprit's hard-drive is still password protected. I'm not sure what I would have done differently, but on the whole this is an immensely rewarding, well-acted and suspenseful drama that highlights the natural advantages women share when they work together.

Carnival Row: Season 1 (2019)

I was immediately excited by the promos and posters for Carnival Row. I mean, a steampunk/fairy tale/Lovecraftian/Victorian gas-lamp fantasy starring Orlando Bloom and Cara Delevingne? Aw yeah, this is my jam.

I was immediately excited by the promos and posters for Carnival Row. I mean, a steampunk/fairy tale/Lovecraftian/Victorian gas-lamp fantasy starring Orlando Bloom and Cara Delevingne? Aw yeah, this is my jam.

Such was my excitement that I was disappointed at the first rather lukewarm reviews, though having watched the first season in its entirety, I really don't get where they were coming from. There are certainly some problems here, but for the most part the pacing, plotting, characterization and world-building is impeccable.

In an alternative world where all manner of fae exist, a war upon the island of Tirnanog forces many of its native inhabitants to seek the safety of The Burgue (London by another name), where they're met with exactly the type of welcome you'd expect.

Given that the English (or Burgish as they're called here) was one of two colonizing forces that caused the war in the first place, the prejudice shown toward the fae is particularly hypocritical, but the oh-so-very-on-the-nose commentary involves overpopulation problems, fae doing menial labour for a pittance, and a variety of culture clashes.

(To be honest, the whole Fantastic Racism thing is wearing a little thin for me by this point – from mutants to androids to fae, I'm reaching my limit on how much hatefulness toward the coded Other I can watch on-screen, so this might be my last show that deals with the subject for a while).

Our protagonists are Vignette Stonemoss and Rycroft "Philo" Philostrate, the former a fae who smuggles refugees to England, the latter a police detective stationed in the titular Carnival Row, where most of the fae immigrants have settled. They have a history together, having fallen in love while Philo was garrisoned at a sacred citadel in Tirnanog, which ended with Philo faking his death so that Vignette could be "free" or some such nonsense - we can all agree that this was a dick move, and the show's attempts to pass it off as the idea of Vignette's friend/former lover didn't convince me for a second.

Orlando Bloom suddenly looks rather craggy, and I remember to my horror that The Lord of the Rings is nearly twenty years old, but he still carries the earnestness of characters like Legolas and Will Turner. Cara Delevingne is always criticized for her acting, but she does great here as the embodiment of the term "fierce."

They cross paths once more when Vignette reaches The Burgue, rediscovering that Philo is not only a policeman but investigating a series of murders that are highly reminiscent of Jack the Ripper.

As well as these, a number of other characters are introduced who have varying degrees of connection to the central murder plot. These include Agreus, a wealthy fae trying to integrate himself into Burgish society, his neighbour, the spoiled Imogen Spurnrose who sees his objective as a way to save the fortunes of her own family, Runyan Millworthy, an impoverished but good-natured fae who unexpectedly gets his fingers in several figurative pies, and the Breakspear family, straight out of a Game of Thrones episode when it comes to political intrigue, comprised of weary patriarch, ambitious mother and ne'er-do-well son.

Jared Harris, fresh off prestige television such as Chernobyl, The Crown and The Terror, looks a little bemused at the fact he’s now talking about pixies and fairies, but still delivers as a noble yet somehow still pathetic tragic figure.

And in a bit of casting coincidence (akin to Patrick Garrow turning up in Reign just as I finished up Killjoys) is Andrew Gower, who I'm currently watching in the second season of Outlander, right before he turned up here as Ezra Spurnrose. This stuff just tickles me.

All of these characters exist in their own subplots, connected through their shared setting rather than narrative purpose, but all help to shed light on the complexities of their world, and have plenty of opportunity to start butting heads in future seasons. There is a mix here of unexpected twists and by-the-books fantasy tropes: for everything I saw coming, something else surprised me.

The world-building in particular is exceptional (along with The Dark Crystal prequel, it's been a good month for that), with different cultures and traditions among the fae and the Burgish subtly injected into the storylines without drawing too much attention to them. For instance, a form of Christianity clearly exists in this world, though Christ is referred to as "the Martyr" and was seemingly hanged instead of crucified, as evidenced by depictions of him hanging from a noose and of priests making circular motions around their necks instead of crossing themselves. Nobody draws overt attention to it; it's just part of world they inhabit.

It's not perfect: despite all the female characters and people of colour, the story eventually settles on the leading white male as the prophesied Chosen One (though granted, we're not entirely sure what that involves as yet) which neatly shunts Vignette out of the position of "co-lead" and into that of "supporting character" in the back half of the episodes.

Likewise, they throw in plenty of unnecessary sex scenes (which prioritize female nudity) and swear words just to remind you that this is Serious Television, even though it isn’t really. And there's something else in way the show handles its Fantastic Racism, which is very difficult to articulate, so bear with me.

By the fifth episode, a pattern emerges in the show's depiction of prejudice against fae that made me feel a little … iffy. It's obvious the writers are trying to highlight the plight of immigrants and refugees, and yet they chose to the muddy the waters of this narrative in several questionable ways. Largely in pitting minority characters, whether they're women, people of colour, fae, or a combination thereof, against each other.

What's depicted isn't the oppressed coming together to beat their oppressors, but rather minorities turning on each other to demonstrate... that they're no better than the Burgish? Is that what the writers are going for?

On some level it isn't an invalid stance to take, especially when you consider that any oppressive system's most powerful tool is the ability to condition the oppressed into resenting each other in order to prevent them from forming alliances, but the show never delves too deeply into that potential theme – which is troublesome considering the most powerful advocate for peace and tolerance is a white dude, sitting pretty at the top of the hierarchy.

It's best seen with the character Sophie Longerbane, the mixed-race daughter of a councillor who is staunchly anti-fae. We're initially invited to empathize with this girl: she's smothered by her father's control and longs for more freedom. After his death, she arrives at Parliament and begins to speak to the assembly, talking about how her mother was ostracized for her race and how it resembled the current plight of the fae.

And then the writers pulls a bait and switch. Sophie then announces that humanity and fae are too different to co-exist, and that the Burgue should do everything in its power to get rid of them. Her own experiences with prejudice haven't imbued her with any compassion for others facing the same kind of bigotry.

We don’t learn anything more about her motivation – I mean, does she truly believe in what she’s saying? In which case she’s a hideous person, especially after explicitly drawing a connection between her own mother and the fae. Or is she just playing along with the status quo, knowing that siding with powerful racists is the best way to consolidate what power she can, aware that the respect they afford her is entirely contingent on her obedience and usefulness?

Because the latter option still makes her a shitty person, but at least has the potential to lead to some interesting places – like for example, how Sansa preferred to seize what little power she could by submitting to the patriarchy that spent the last eight seasons trying to destroy her, over allying herself to the foreign queen who approached her with a plea to their shared femininity.

Of course, then the show ends, denying us the chance to see how Sansa fares with this life-long decision, but perhaps the idea will be explored further with Sophie in later seasons. There's plenty of material in the inherent tragedy of powerless minorities attempting to garner some degree of agency by playing to their oppressors and stepping on their fellow oppressed, but we'll have to wait and see whether the show is in fact aiming for: “look at what oppressive systems do to people – rob us of compassion and make us turn on each other just to survive” or whether it's just: “everyone is bad and nasty because of their greedy lust for power, and minorities are no better than their oppressors for trying to attain it!"

The Dark Crystal: Resistance (2019)

This was everything I wanted and more! Like most eighties kids, I grew up watching The Dark Crystal, and though there were rumours about ten years ago of a movie sequel, it never came to fruition (though the script has since been adapted into a graphic novel).

This was everything I wanted and more! Like most eighties kids, I grew up watching The Dark Crystal, and though there were rumours about ten years ago of a movie sequel, it never came to fruition (though the script has since been adapted into a graphic novel).

And so when Netflix announced its intentions to produce a Dark Crystal prequel, it was like a dream come true. There was a hush over the proceedings for a long time, and then the trailer dropped – and it was incredible.

Anyone who has seen the 1982 film knows that a prequel could only ever end in tragedy, given that the original movie has only two Gelfings left alive in the world; their communities and culture otherwise utterly wiped out by their Skeksis overlords. This story is set about a thousand years before that, in which the Gelfings were strewn across the planet of Thra in thriving tribes and settlements.

But they live under the delusion that the Skeksis are their protectors, safe-guarding the titular Crystal for the benefit of all. In reality, the greedy and corrupt Skeksis are using its power to attain eternal life, and integrated the Gelflings into a system that ensures their servitude, obedience and tribute. And when the Skeksis discover a way to utilize the very lives of the Gelfings in order to extend their own, the entire species is put at risk.

It's up to just a few Gelfings who discover the truth to spread the word and organize resistance. Unfortunately, their greatest obstacle is not the Skeksis, but rather their fellow Gelfings, many of whom have been too deeply indoctrinated into the worldview imposed upon them to believe anything else.

The main characters are comprised of that still-rare combination of one male (Rian, a guard at the Castle of the Crystal) and two females (Brea, a Gelfing princess, and Deet, a member of the secretive underground Grottan clan) who initially form their own suspicions regarding the Skeksis, and eventually cross paths in order to share intel.

The story struggles a little regarding what it knows its endgame must be, concluding on a note that tries to be hopeful even as the audience knows it's all downhill for the Gelfings after that point. The show's true value lies in its artistry and world-building, which are an absolute feast for the eyes and imagination. As with the original film, everything in this world is crafted by hand and brought to life by puppetry, from the flora to the wildlife to all of the main characters, which incidentally look much more expressive than they did back in the eighties.

Granted, there is a smattering of CGI here and there, but the creators knew that the hook of any Dark Crystal story would have to be the puppetry. They also take the opportunity to really flesh out the culture of the Gelflings themselves, and the best part is their decision to make theirs a matriarchal society.

All of the clans are therefore ruled by queens (called Maudras, which seems to be etymologically derived from Aughra, the embodiment of the planet itself, suggesting remnants of a culture which predates the arrival of the Skeksis), which means an abundance of female characters voiced by actresses such as Helena Bonham Carter, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Caitronia Balfe, Alicia Vikander, Hannah John-Kamen, Natalie Dormer and Lena Headey, as well as the aforementioned female protagonists Anya Taylor-Joy and Nathalie Emmanuel. Wow!

That's not even getting into some of the fun prequelly stuff they do, as when the Mystics finally turn up and Aughra awakens from her centuries-long sleep. That said, they do end up giving away the twist that lies at the heart of the film, so I'm sure debates will rage regarding what order the show and film should be watched in.

Occasionally the Skeksis scenes drag on too long (and one constantly has snot dripping out of its nostrils, which was hard to look at) and I didn't totally buy Tavra's character arc (she gets off WAY to easily for the shit she pulled) but it felt so damn good to be back in Thra, truly one of my favourite fictional worlds.

Always seemed a little odd to me that Anthony Horowitz had such huge success with Foyle's War since it began in 2002, and yet he only successfully broke into novels for adults a few years ago...

ReplyDeleteI have some thoughts as to what you will make of The Secret Commonwealth (especially since I see we both largely thought the same things about LBS). But I will say no more for now.

Unbelievable was just amazing, wasn't it? Merritt Wever in particular was a revelation (I'd never seen her in anything before either), being tough as nails (the dressing down of her subordinate would never have been allowed by a lesser showrunner/writer for fear of making her "unlikable") but also her quiet, soft spoken strength dealing with the victims, and the show's complete lack of interest in spending time on the rapist and his justifications was a great choice. And yet it didn't fall into the pattern of girlz rule boyz drool narratives - the male intern was allowed to be capable and his work led to a break in the case, and the foster mother's prejudice contributed to Marie's persecution as you said.

ReplyDeleteI really loved Carnival Row, but agree it lost its way a bit in the back half. But I was willing to forgive quite a bit for a show willing to take a chance in a world of sequels, reboots, and remakes. Orlando Bloom is best suited to these kind of brooding roles, and I've never cared for Cara Delvingne but thought she was fantastic as Vignette, and it was nice to see Tamzin Merchant again!

And of course, The Dark Crystal. The higher ups over at Lucasfilm could certainly take some pointers about how to expand on an existing property while respecting the original. I started watching not expecting much, but was hooked by the end of the first episode. It's clear so much care was taken not just with the worldbuilding and explanatory nature of a prequel, but to actually concentrate on the characters as the heart of the story and allow them to drive the narrative. And of course, the wonderful, varied female characters actually allowed to interact with one another and have fully realised character arcs (again, Lucasfilm take note).

Having not seen the original film in years, I rewatched it immediately after finishing the series and despite the obvious advances in puppetry and technology, it is near seemless (the evolution of the Garthim, Jen and Kira visit the ruins of the Stonewood clan etc), and rather harrowing to see Thra reduced to a stormy desert after seeing it thriving and green.

Although I didn't get the impression it was set so far before the film? I assumed that the gelfing genocide happens within a fairly short time period (50-100 years), and based on Deet's vision there's a good chance Jen and Kira are the next one or two generations down from the trio (if not directly related).

Merritt Wever in particular was a revelation (I'd never seen her in anything before either), being tough as nails (the dressing down of her subordinate would never have been allowed by a lesser showrunner/writer for fear of making her "unlikable") but also her quiet, soft spoken strength dealing with the victims

DeleteShe was SO GOOD. I had a look at her IMDB page and her biggest role seems to have been in The Walking Dead, which I have no interest in watching, so hopefully this will get her some bigger roles.

And of course, the wonderful, varied female characters actually allowed to interact with one another and have fully realised character arcs (again, Lucasfilm take note).

I loved the whole thing so much. It's amazing how one seemingly small world-building choice (Gelfings are matriarchal) can exponentially change the role and importance of female characters in a story. To see more and more women getting introduced with each episode was just mind-blowing.

Although I didn't get the impression it was set so far before the film?

Yeah, you're probably right. Honestly, I'm not sure how I reached that number. Maybe it's just horribly sad to think of all that beauty and culture wiped out over the course of just a few generations.