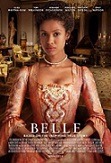

Last week I took my mother to see Belle as a belated Mother’s Day gift, and my advice to you is to please find a way of seeing this film. It hasn’t been given a lot of publicity, but it really is worth making the effort to track down and watch on the big screen.

Some spoilers below...

As you probably know, Belle is based on the true story of Dido Elizabeth Belle, the illegitimate daughter of Admiral John Lindsay and an enslaved African woman. As a child she was sent to live with her father’s uncle William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, who raised her as a free young gentlewoman at Kenwood House. It’s not hard to believe in Providence when you consider that Lord Mansfield, in his capacity as Lord Chief Justice, was later called on to rule in the case of the Zong Massacre.

This was a controversial court case that followed the deaths of approximately 142 enslaved Africans on board the slave ship Zong in 1781. A slaving-trade syndicate had taken out insurance on the lives of the slaves, and after running low on water and having made several navigational mistakes, the crew threw many of the slaves into the sea to drown.

J. M. W. Turner's The Slave Ship, inspired by the Zong Massacre

According to what records remain, 54 women and children were thrown through cabin windows into the sea on the 29th November, followed by 42 male slaves on the 1st December. 36 followed in the next few days, and another ten, in a display of defiance, threw themselves over board.

It’s harrowing stuff, especially since the owners of the Zong went on to make a claim to their insurers for the loss of the slaves. The insurers refused, claiming that the slaves (many of which were diseased) were deliberately murdered after being deemed worth more dead than alive.

This is the backdrop of Dido’s story, one that provides the film’s climax and is very much linked into her journey to find a place in the world. As such, there are two main (though interconnected) threads running throughout the film: that of Gugu Mabatha-Raw’s eponymous Dido Belle trying to find her place in the world, and the court proceedings surrounding Lord Mansfield’s ruling on the Zong trial.

Lord Mansfield (Tom Wilkinson) and his grand-niece Belle (Gugu Mabatha-Raw)

Dido’s position in 18th century English society is one of the most fascinating things about the film, demonstrating just how strange and arbitrary the rules governing her existence really were. She’s too high-born to eat with the servants, yet the colour of her skin prevents her from dining with the family. Lord Mansfield considers clergyman John Davinier to be an unworthy suitor because he is not as high-born as his great-niece is, even as Lady Mansfield resigns herself to the fact that Dido will probably never wed. Because she is her father’s only heir, she inherits a fortune while her cousin is left virtually penniless after her father remarries and has more sons. This in turn renders Dido the more desirable prospective bride despite her mixed-parentage and illegitimacy.

Just as interesting is the way Dido is treated by those around her. In a society that accepted slavery as a way of life, it seems strange that Dido would be more-or-less accepted into upper-class society. Over the course of the film, she experiences overt racism from only one other character (and even he keeps most of his hatred to himself for the film’s duration).

Yet prejudice is not always hostile, and the film is careful to portray Dido’s position in society as “the exception to the rule.” The subtext is that white society can tolerate, or even embrace, “the exception” that is Dido among their ranks – just as long as the majority of the black population remain servants and slaves. And though Dido is very sheltered, she still lives within the confines of prejudice which does not cease to be insulting just because it is polite. Dido’s potential mother-in-law Lady Ashford initially treats her as a curiosity, whilst her sons Oliver and James describe her as “exotic” and “repulsive” respectively. When it becomes apparent that she’d make a lucrative bride, Oliver tells her with heartfelt sincerity that he can overlook her mother’s colouring, loving her in spite of her mixed-blood rather than because of it.

Did I mention costume porn? Because there's a LOT of costume porn.

But of course, this is where the Zong Massacre comes in. Out of love for her, Lord Mansfield tries to shield her from the realities of the world, telling Dido nothing of the massacre or what it might mean for her. But when Dido seeks out the truth from John Davinier, she becomes achingly aware of what her life would have been like were it not for her father’s intervention and her great-uncle’s kindness. It’s not enough for Dido to be “the exception” anymore, and having pondered the words of her cousin Elizabeth (a girl desperate for marriage to secure her well-being) she considers herself twice freed: from the lower-class citizenship of other black people around her, and – due to her inheritance – from the necessity of marriage.

Circumstances have given her a unique voice, but what can she do with it?

Toward the end of the film the focus is just as much on Lord Mansfield’s moral crisis regarding the Zong Massacre as it is on Dido’s awareness of her quasi-privilege and growing sense of identity. Perhaps the slight shift to Lord Mansfield was inevitable considering the importance that the film places on the court case, but though the decision ultimately lies with Lord Mansfield, the film gives Dido some agency in smuggling her great-uncle’s notes to Davinier, makes sure that she’s present in the courtroom when the verdict is announced, and opens up the question of just how influenced Lord Mansfield was in his decision by her role as his beloved grand-niece.

But the greater part of the film remains with Dido, her love story with John Davinier, her relationship with her cousin Elizabeth, and her struggle to find a place in society. Since the film was inspired by the 1779 portrait of Dido and Elizabeth, I was glad that a lot of emphasis was put on their bond with each other – in fact, Elizabeth’s feelings toward Dido probably comprise the most shrewd depictions of race-relations in the film.

Whereas Davinier ends up perhaps just a little bit too good to be true (more on him in a bit), Elizabeth epitomizes the whole “I don’t notice race” way of thinking. This makes her refreshingly unprejudiced as a child, but also utterly ignorant as to many of the difficulties that Dido faces as an adult.

Dido Belle (Gugu Mabatha-Raw) and Elizabeth Murray (Sarah Gadon)

Elizabeth is bewildered by Dido’s reaction when she displays anxiety over the portrait that’s to be painted of them. Though Elizabeth is constantly frustrated over Dido’s exclusion from the dinner table, she doesn’t really question it to any great extent. During a fight between the girls, there is a moment of suspense when Elizabeth is clearly gearing up for an accusation of Dido’s unworthiness as a wife, but ultimately comes out with “you are illegitimate” instead of “you are black”. There’s never a chance for Elizabeth to react to the finished portrait of the two girls together, but when Dido is moved to tears by her placement at Elizabeth’s side, you just know that Elizabeth would simply wonder: “well, why wouldn’t she be placed beside me?” Race is never an issue to Elizabeth.

But the profound innocence that she displays in regards to Dido’s race isn’t as heart-warming as it might sound. It places a gap between the girls that’s never fully bridged, for the fact that Elizabeth considers Dido’s skin-colour completely unimportant means that she has little to no understanding of her struggles.

Perhaps the most poignant scene illustrating this point is when Dido is struggling to brush her hair, only for a black servant to enter the room and tell her that she should start from the ends. We then cut to a scene in which she’s doing precisely that, while Elizabeth hovers in the background, curious but uncomprehending as to why Dido is so delighted. You can see it for yourself right here:

It’s possible to love a person with fully understanding them, and this is the case with Elizabeth towards Belle.

It’s in this that Elizabeth provides a foil for John Davinier, a man who is written as someone who can not only emphasize and understand the difficulties Dido faces, but is passionate about bringing an end to the slave trade. He probably bears little resemblance to his real-life counterpart, and it’s difficult to really comment on him considering he’s designed more as Dido’s ideal partner than a three-dimensional character in his own right, but as it happens – I don’t care. The film choses to give Dido a husband who was worthy of her, and whose eyes were open to how she had to live in the world. Why shouldn’t she have a quintessential fairytale ending? The film is pretty unapologetic about giving her one.

Belle and John Davinier (Sam Reid)

And yet for all the sweeping romance, Elizabeth and Dido are very much the focal point of the movie, and it’s a beautiful choice to have the film close on the portrait of the two of them (with details of their later lives superimposed over the top of it). I went out in search of the portrait on-line just to get a better look, and it is quite a striking picture, with the composed and seated Elizabeth contrasted with the more spritely and active-looking Dido. According to art studies, the fact that Elizabeth’s hand rests upon Dido’s waist is a suggestion of affection and equality (rather than a depiction of her being pushed away, as it appears at first sight).

So to sum things up – go see this film. Gugu Mabatha-Raw is an actress that’s always been close to my heart, as she’s the visual model I have for one of my own original characters. Seeing her here in period gowns was a real treat, as well as inspirational in getting a fix on my own character. But she’s also a lovely actress, and throughout the course of the film she captures Dido’s confusion, yearning, sadness and humanity in negotiating a world that doesn’t necessarily reject her, but doesn’t really have a place for her either. You’re never entirely sure how she’s going to react to any given situation, for though she’s perfectly comfortable giving orders to a multitude of white servants, she is rendered awkward and speechless when coming face-to-face with a black woman who works in the family’s London abode.

Tom Wilkinson steps up to second base as Lord Mansfield, and gives a very dignified, low-key performance as an aging man whose fires are gradually being extinguished, weary with the state of the world and yet whose love for Dido is something that causes him pain and joy in equal measure. Ultimately his court ruling is framed as him choosing to do right by her as well as following his own conscience, and their held gaze after the verdict is probably the most heart-rending part of the film (even more so than Davinier/Dido’s declarations of love).

Miranda Richardson, Emily Watson and Penelope Wilson, plus Sarah Gadon and Gugu Mabatha-Raw in the background.

Sarah Gadon balances Elizabeth’s sweet nature with a certain amount of ditziness without going overboard in either direction, and Miranda Richardson, Emily Waston and Penelope Wilson all have supporting roles. They’re old pros, but they know the film belongs to Gugu and don’t try to steal her spotlight, though Watson and Wilson are each given an effecting scene in which the former appeals to her husband on the Zong Massacre ruling, and the latter recalls a lost love from her youth. It appears that Tom Felton is well and truly typecast as the upper-class jerk, but hey – it’s not like he’s not good at the role, and there’s a moment in which where he comes across as truly frightening, above and beyond anything Draco Malfoy was capable of.

Director Amma Asante

Directed by Amma Asante and written by Misan Sagay (both women of colour) means that there is a personal element to the film that you can just feel. There are so many little moments of insight and detail that almost certainly wouldn’t have been present if this was in the hands of anyone else, such as an-almost throwaway moment in which Dido describes a book she’s reading, one which involves a black man marrying a white aristocrat. Her uncle asks her if she can see herself in such a story, and she answers that she doesn’t really see herself anywhere. It’s pertinent to her character, but it’s also a subtle commentary on the lack of representation of black women in the media, slipped in so gracefully that you hardly notice it.

And for anyone who just loves Jane Austen-esque period films, there’s an abundance of beautiful costumes, set-design and locations to provide the requisite eye candy. With its female lead, eye on social issues, costume porn and highly invested cast/crew, this is one of those movies that internet fandom keeps insisting that it wants, and yet duly ignores once they actually get it.

Go and see it.

No comments:

Post a Comment